Cost Structure Analysis

Fixed Costs vs. Variable Costs

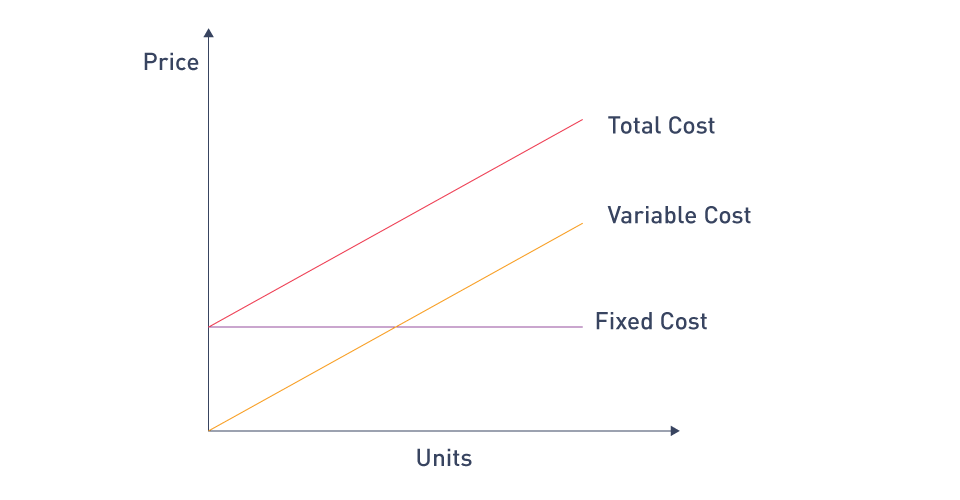

Comprehending the differences between fixed and variable costs is essential for efficient financial planning and operational management in the context of electrical systems.

Fixed Costs: Expenses that remain constant regardless of the amount of power produced or used are known as fixed costs. Regardless of how much electricity is produced or sold, these expenses must be paid. In electricity networks, examples of fixed costs are as follows:

- Capital Costs: The outlay of funds needed to construct infrastructure, such as substations, transmission lines, and power plants. This covers the price of the land, the machinery, the building, and the engineering services.

- Maintenance Costs: Regular infrastructure maintenance and upkeep, which usually do not change in response to output levels and guarantee that all components are safe and operational.

- Administrative Costs: base pay for managers and administrative employees, office supplies, and other recurring overhead expenditures.

- Depreciation: The slow deterioration of tangible assets over time as a result of aging, obsolescence, or other causes. Over the asset's useful life, this cost is dispersed.

Figure 7: Fixed vs. variable costs

Variable Costs: The amount of electricity produced or used directly affects variable costs. These expenses go up with rising production and down with falling production. In energy systems, some instances of variable costs are as follows:

- Fuel Costs: The price of fuel used in power plants, such as coal, natural gas, and uranium. For thermal power plants, fuel expenses make up a sizable portion of the variable costs.

- Operating Costs: Outlays for lubricants, water for cooling systems, and labor for operational staff that are necessary for the regular running of power plants.

- Transmission and Distribution Costs: These are the expenses incurred in the transfer and distribution of electricity, encompassing systemic energy losses as well as grid management and balancing costs.

Utilities are able to price electricity, budget, and plan financially by comprehending the equilibrium between fixed and variable costs. It is imperative to ensure the economic sustainability of electricity systems and maintain profitability through the effective administration of these costs.

Marginal Costs and Average Costs

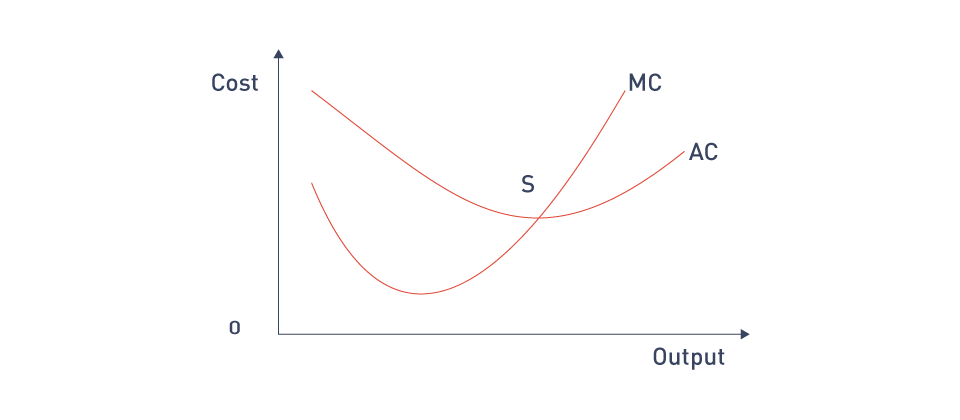

Marginal Costs: The price of generating one more unit of electricity is known as the marginal cost. It shows the additional expenses incurred when one unit of manufacturing is increased.

$$\text{Marginal Cost} = \text{Total cost of the } n^{\text{th}} \text{ unit} - \text{Total cost of the } (n-1)^{\text{th}} \text{ unit}$$When it comes to electrical systems, the variable costs that come with producing more power—like fuel and operating costs often determine the marginal cost. The kind of power plant and fuel utilized can have a big impact on marginal costs. For instance, because they don't consume fuel, renewable energy sources like solar and wind have extremely low marginal costs, but fossil fuel-based plants have greater marginal costs because they utilize fuel. In competitive energy markets, where prices are frequently determined by the marginal cost of the final unit produced, marginal cost pricing is crucial. This price mechanism signals the cost of raising supply to match demand, ensuring the market runs smoothly.

Average Costs: The calculation of average costs involves dividing the total cost of production by the quantity of units produced. It gives an estimate of the fixed and variable costs associated with producing one unit of electricity.

$$\text{Average Cost} = \frac{\text{Total cost}}{\text{Total units produced}}$$As production grows, the average cost decreases due to the dispersion of fixed costs over a larger number of units. This is known as the economies of scale. Utilities use average cost calculations to assess the overall effectiveness of their operations and establish pricing that balances total costs with a sustainable return on investment. Average cost pricing can be used in regulated markets to set tariffs that guarantee utilities make a reasonable profit and recover their costs.

Relationship Between Marginal and Average Costs: When making decisions about electricity networks, it is important to consider the link between marginal and average costs. Production of more units will lower the average cost, exhibiting economies of scale when marginal costs are lower than average costs. On the other hand, producing more units will raise the average cost if marginal costs are higher than average costs.

Figure 8: Typical marginal cost (MC) vs. average cost (AC) curve

Utility companies aim to operate efficiently by producing at a level where their marginal costs match their average expenses. The lowest cost per unit of production is represented by this point, sometimes referred to as the least efficient scale, which serves as a gauge of ideal production efficiency.

Revenue Generation Mechanisms

Tariffs and Pricing Structures

Tariffs and pricing structures are essential for generating money in the operation of electrical systems. They set consumer power prices and make sure utilities can make a profit that is both appropriate and covers their costs.

Tariffs: The prices that customers pay for the electricity they use are known as tariffs. These rates can be set up in a variety of ways to represent diverse pricing structures, consumption trends, and policy goals. Typical tariff kinds are as follows:

- Flat-Rate Tariffs: One rate per unit of power used, irrespective of usage volume or time of day. Though it's basic and simple to grasp, this structure doesn't reflect the variable costs associated with producing electricity or promote energy conservation.

- Tiered Tariffs: Various prices are imposed based on varying usage levels. For example, a lower rate may be applied to the initial block of consumption, and larger rates may be applied as consumption increases. This arrangement can encourage energy efficiency by providing users with incentives to use less electricity.

- Time-of-Use (TOU) Tariffs: These rates change according to the time of day, taking into account variations in the cost of producing power. Peak demand periods are associated with higher rates, while off-peak periods are associated with lower rates. TOU rates encourage users to move their consumption to off-peak times, which helps balance demand and ease grid load.

- Seasonal Tariffs: Seasonal fluctuations in production costs and demand are reflected in the use of different rates. For instance, during the summer, when air conditioning use raises the demand for power, higher rates may be applied.

- Demand Charges: Some tariffs contain demand charges based on a consumer's peak power demand in addition to energy consumption charges. Commercial and industrial clients are accustomed to this structure, which encourages them to control and lower their peak demand.

Pricing Structures: While encouraging the efficient and fair use of the electrical system, pricing structures are intended to guarantee that the costs of producing, transferring, and distributing power are sufficiently repaid. Important things to think about while creating price systems are as follows:

- Cost Reflectiveness: Prices ought to account for all actual expenses incurred in the provision of electricity, such as those related to production, transmission, distribution, and administration. With this strategy, the costs that users place on the system are distributed fairly to the users.

- Equity and Fairness: To guarantee that all customers have access to reasonably priced power, pricing systems should be fair and equitable. To maintain equity, special tariffs or subsidies might be created for low-income households.

- Incentives for Efficiency: Prices ought to encourage consumers to utilize energy more wisely and cut down on waste. Tariffs on goods and services, tier-based tariffs, and other policies that promote conservation and demand-side management can be used to accomplish this.

- Simplicity and Transparency: Pricing schemes and tariffs must be simple enough for customers to comprehend. Pricing transparency fosters consumer acceptability and trust.

Market Mechanisms

Market mechanisms are important for revenue generation and the overall economic efficiency of electricity networks, in addition to tariffs and pricing structures. Through competitive processes, market mechanisms enable the purchasing and selling of power, guaranteeing that prices accurately represent supply and demand dynamics.

Wholesale Electricity Markets: These markets facilitate the efficient matching of supply and demand by allowing generators and retailers or utilities to trade electricity in large quantities. These markets include capacity and ancillary services markets that guarantee long-term grid stability and reliability, as well as day-ahead and real-time markets where power is bought and sold for near-term delivery.

Retail Electricity Markets: Instead of being dependent on a single utility provider, customers in deregulated markets have the freedom to select their electricity suppliers from a competitive field. Suppliers provide a range of programs, frequently with varying contract periods, renewable energy sources, and price structures. Retail marketplaces strive for greater competition since it can result in more options for customers, inventive services, and lower costs.

Table 1: Wholesale vs. retail electricity markets

| Aspect | Wholesale Electricity Market | Retail Electricity Market |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The market where electricity is traded in large quantities, typically between power generators and bulk buyers like utilities or large industrial consumers. | The market where electricity is supplied directly to end users, such as residential, commercial, and small industrial customers. |

| Participants | Generators, wholesale traders, utilities, and large industrial consumers. | Retailers, utilities, end consumers (residential, commercial, industrial). |

| Pricing Mechanism | Prices are usually set through auctions, contracts, or spot markets and fluctuate based on supply and demand dynamics. | Prices are determined by retail tariffs or negotiated contracts, which can be either fixed or variable. Retail pricing is often influenced by fluctuations in wholesale market prices. |

| Market Structure | Involves competitive bidding or spot market transactions, where prices are volatile and shaped by shifts in supply and demand. | The market can be regulated or competitive, with retailers offering different pricing plans and services, often influenced by wholesale market conditions. |

| Contract Types | Involves long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), short-term contracts, and spot market transactions. | Includes fixed-rate plans, variable-rate plans, and time-of-use (TOU) pricing plans. |

| Regulation | Regulated by organizations like independent system operators (ISOs) or regional transmission organizations (RTOs), with market rules and price formation managed by regulatory authorities. | Regulated by utility commissions or energy regulators, which monitor tariffs, consumer protection, and market practices. |

| Transparency | Market prices and transaction details are usually more transparent, with price indices and market reports available. | Retail pricing can be less transparent, with many tariff structures and promotional offers. |

| Risk and Volatility | Involves higher risk due to price volatility influenced by market conditions, weather events, and fluctuations in demand. | Consumers with fixed-rate plans face more predictable risks, whereas variable-rate plans expose them to fluctuations in wholesale prices. |

| Purpose | To manage supply and demand on a large scale and ensure efficient generation and transmission of electricity. | To deliver electricity to end users while providing options for pricing and service selections. |

| Market Access | Typically available to large-scale entities and traders. Smaller entities may access the market through intermediaries or financial instruments. | Available to all end-users, with several options to choose suppliers or plans based on their choice and usage patterns. |

| Impact on Consumers | Has a limited direct impact since prices are passed on to retail consumers, but it indirectly influences retail prices and reliability. | Has a direct impact, as consumers are billed for their electricity usage and influenced by retail pricing structures and the quality of service. |

Regulatory Oversight: To maintain fair competition, stop market manipulation, and safeguard consumers, regulations are in place for both the wholesale and retail sectors. Regulators create policies and procedures for the market, keep an eye on consumer behavior, and impose rules compliance.

直接登录

创建新帐号